When I moved to Ukraine, I had to learn a whole new Ukrainian vocabulary. It turned out that I had grown up speaking a Galician/diasporic Ukrainian, which used many dialectisms, Polonisms, and archaisms. To keep track of the differences between the two lexicons, as well as to document the way my family spoke, I started to put together a dictionary.

I ended up with a rather comprehensive list, and since I know many other families in the Ukrainian diaspora use a similar lexicon to the one I grew up with, I decided to make it public. Ultimately, it’s an attempt to help preserve the western Ukrainian dialect that is still spoken in North America, but which is slowly being lost.

This, of course, is not the first project to create a dictionary of words from various Ukrainian dialects. There have been many lists of Lviv or Galician words published online, such as this one, as well as books such as Gvara, and a comprehensive 800+-page dictionary called Лексикон Львівський. The latter (pictured) contains many of the words in my list, but not all. Thus, I feel there is still a need for a similar project focused on the diaspora language.

The Galician Dialect

For historical reasons, a distinct dialect of the Ukrainian language emerged in Galicia. Since Ukrainians in Galicia lived in close proximity to Polish-speakers and the Polish language—there were many intermarriages, the official and dominant language in towns and cities was Polish, etc.—the Galician dialect has many similarities to the Polish language.

Furthermore, Galicia, as opposed to much of the rest of Ukraine, was never part of the Russian Empire and so Ukrainians in Galicia had fewer restrictions on their language and experienced less Russian influence. Once Galicia joined the rest of Ukraine in the Soviet Union, however, the language there too started to change, due to Russification, standardization, and the natural evolution of language.

As part of russification, major changes were made to the orthography of the language, and together with these changes, more and more russian words were introduced, replacing Ukrainian words as the only accepted variants.

The Ukrainian Diaspora

On the other hand, the Galician dialect, including its lexicon, accent, and orthography, was rather well preserved in the diaspora.

Several factors contributed to this, including:

- The high concentration of Galician Ukrainian immigrants in many diaspora communities

- The rather static evolution of the language in the diaspora and its retention of certain archaic words, especially those related to technology (for example, “загасити світло” (“extinguish the light”), which harks back to a time when fire was used for lighting, or the word “перо,” which implies a “quill pen”)

- The absence of the Russification of the language in the diaspora (the diaspora continued to use the first pan-Ukrainian orthography of 1928 until this day, never adopting the Russified orthographies used in Soviet Ukraine and still largely used there today).

To clarify, when I use the word “diaspora” here I mean specifically the community that descended from the third wave of immigration (1940s-1950s), many of which came from western Ukraine, in particular Galicia. Though as the two prior waves of immigration also originated in western Ukraine (Galicia, Bukovina, Subcarpathia), the older Ukrainian communities probably spoke (and speak) quite similarly. However, it was the members of the third wave who eventually came to dominate community life in several regions of North America, especially in cities like Chicago.

I grew up in the Ukrainian community in Chicago, where many of the Ukrainian organizations such as Ridna Shkola, Plast and SUM, used a language/dialect similar to the way my family spoke. Thus even if someone had ancestors from central or eastern Ukraine, they were likely exposed to the Galician language if they were involved in the community. In fact, my paternal grandmother was from central Ukrainian and came from a Russian-speaking family, but her husband was from the Boyko region of the Carpathians and so for the most part she picked up the western Ukrainian dialect.

Galicia Today

Some of the “diaspora” words can be heard today in western Ukraine, but generally only in rural areas and from the older generations. Thus even in the region of its origin, the dialect (especially heard from a young person) sounds rather archaic and old-fashioned to the average Ukrainian. While some of the words are in fact archaisms, most are just dialectisms (or even just original Ukrainian words) that were preserved in the diaspora but lost in Ukraine.

There are, however, a handful of these words that are used widely among all generations in Lviv and other Galician cities (for example, “ровер”). Other words are finding their way back to the modern Lviv language as there is a heightened interest in the old Lviv, the old language, and for example many new restaurants and cafes have chosen to use precisely these old Lviv/Galician words in their menus.

Galician Syntax and Phraseology

In addition to lexical and orthographic differences, I’ve noticed several other features of the diaspora language that differ from the Ukrainian spoken in Ukraine. These include certain phrases, sentence constructions, and other practices. I’ve also included these in the dictionary.

Some of the key differences I’ve noticed:

- мати vs. y мене

To mean “I have,” we more commonly use the very “мати” (я маю) rather than the “y мене.” - є vs. no є

We more commonly use “є” to mean “is/are.” In Ukraine, it is typically dropped, or replaced by a dash. Furthermore, we more often use the nomіtive rather than the genitive when using “є.” For example, in the diaspora we would say “Я є веселий мандрівник” while in Ukraine one would say “Я веселий мандрівник or Я є веселим мандрівником???? - чи vs. no чи

We almost always use “чи” at the beginning of questions, whereas in Ukraine “чи” is often dropped, which is closer to russian. - мусiти vs. мати / треба / потрібно

To say “I have to/need to,” we more commonly use the verb “мусiти” rather than “мати / треба / потрібно” (e.g., “я мушу” rather than “я маю” or “мені треба/потрібно.” (While the verb “мусити” is used in Ukraine, it’s spelled with an и while we spell and say it with an i.) - preposition “до” + genitive

We tend to use the form “до” + genitive (“до школи,” “до Києва”) as opposed to the preposition “у” + accusative (“у школу,” “у Київ”). - пан/панi + vocative case vs first name + patronymic

We address someone as пан/панi + vocative case (e.g., Пані Оксано). We never use first name + patronymic to address someone, which is common in Ukraine. However, at least in western Ukraine, I am noticing a shift toward the former. - прошу vs. будь ласка

We typically say “прошу,” rather than “будь ласка”

Comparison to Polish and Russian

For many of the words in my dictionary I added the Polish and Russian translations. Using this comparison, one can notice that a majority of the “diaspora” words are similar to Polish, and many of the “standard” Ukrainian words are similar to Russian. That said, by no means are all such cases Polonisms or russisms, but one must keep in mind that Polish had a significant influence on the language spoken in western Ukraine, and that the Ukrainian language did undergo heavy Russification, which after WWII affected the language spoken in western Ukraine (and so there are a lot russisms).

The book Contested Tongues: Language Politics and Cultural Correction in Ukraine by Laada Bilaniuk covers some specifics about the russification of Ukrainian. A few examples can be found in this table:

Nonetheless, there are cases when the opposite is true—when the “diaspora” word is closer to both Polish and Russian than it is to standard Ukrainian (for example, “важне”), or closer to Russian than to Polish or standard Ukrainian. This may be explained by the fact that it is just an older Slavic word, as Andrew Sorokowski wrote in a comment under one of my previous posts: “some Old Galician words strike modern Ukrainians as russified, such as ‘vozdukh’ for ‘air’; there, however, are Old Church Slavonicisms, disseminated by the Greek-Catholic clergy in the 19th century.”

It’s also interesting to see when a word in one language has a completely different meaning in another (for example, “склеп”).

Thus, except for a few obvious cases, I cannot say when a word is a Russism, Polonism, or just an older Slavic word. In any case, I don’t want to prove any dialect or word is better or more authentic, but rather want to have a visual comparison of the languages.

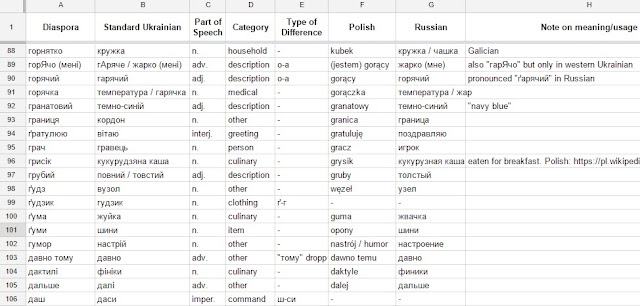

The Diaspora Dictionary

All in all, I have a compiled comprehensive list with almost 700 words, which I made on Google Spreadsheets. For many words, I’ve also included the Polish and Russian translations, as well as a comment on the meaning or usage. The list can be sorted by category, part of speech, type of change, etc., which can be used to find trends.

The “Diaspora” column is for the most part the way my family speaks. In most cases the words are common among the “diaspora,” but there may be some cases where specific words are only known/used by my family.

In the “Standard Ukrainian” column I tried to add the most accepted/standard word currently used in Ukraine, but sometimes I added a word that I hear the most, even if it may not officially be the most correct.

In addition to different words, I’ve also included words or phrases that are declined differently as well as differences in some common phrases and sayings.

There are of course cases where the standard Ukrainian word is known and used in the diaspora as well.

There may be some mistakes in the Polish and Russian columns, as I am not fluent in either. I had some help from friends, but also some help from Google Translate.

I welcome any corrections or comments, as all of the above are just my observations. I will continue to add to the list and make corrections.

For a link to the the full online dictionary, CLICK HERE

By Areta Kovalska

While I appreciate your work – for me it is more important that my grandchildren and great-grandchildren learn, speak and communicate among themselves in Ukrainian – Galician or any other accent is not important. I arrived in 1948 – do speak Ukrainian the way my grandparents spoke in Halychyna and the way my aunt and uncle (with whom I arrived in Canada) spoke and even taught in schools – because they were originally teachers in Ukraine. I am proud of the fact that my children and even great-grandchildren speak, write in Ukrainian and having attended 12 years of Ukr Saturday schools – know Ukrainian history and literature better than I, since my Ukrainian education was interrupted by Second World War. I know of many Ukrainian families of 4-th Waive Immigration – who say “why do our children need Ukrainian, they are living in Canada” – so their proper accent .does not seem to do any good at all. I do hope that our Galician Accent does not vanish but continues to linger in the Diaspora. I am proud of it – The pioneers with this Galician Accent built churches and Domivky, which the newcomers take for granted and in most cases do not contribute financially or culturally.

I think it’s wonderful that even after so many decades and generations, Ukrainian is spoken by these families and that the Galician accent, dialect, and traditions have also persevered and I hope that they continue to do so

Would Galician Ukrainian be the same as Rusyn/Ruthenian? That would be the language my family spoke.

i quess yes? because Galucian Ukranian in the same dialect family as Guzulskiy

Why do people assume that words which are “closer to Russian” are due to Russification? Ukrainian, Belarus and Russian are from the eastern slavic group of languages, and thus share many words; Polish is from the western group, so there would be less natural overlap with Ukrainian. And, if there is a question, an etymologic dictionary can help sort out word origins (whether the word has deep slavonic roots or is a loan word).

Diasporan Ukrainian comes in multiple varieties, with many sources: Halychana (“Galician”), Volyn and environs, and “Velyka Ukraina” (eastern and central Ukraine) are three. Volyn, unlike other areas of west Ukraine, is predominantly orthodox and has been under Russian control (alternating with Polish); its vocabulary has western and eastern influences/words. There was Polonization, but less so than in Halychyna. (It was the language of my childhood.)

A hallmark of the Galician diasporan dialect is a marked linguistic lisp–diasporan speakers pronounce the “c” (s) as a “sh” when followed by the softening sign or і, я, ю.

I did note in my article that not all words which are closer to Russian are due to Russification: “In fact, it’s interesting to see cases where the opposite is true—where the “diaspora” word is closer to both Polish and Russian than it is to standard Ukrainian (for example, “важне”), or closer to Russian than to Polish or standard Ukrainian. This may be explained by the fact that it is just an older Slavic word, as Andrew Sorokowski wrote in a comment under one of my previous posts: “some Old Galician words strike modern Ukrainians as russified, such as ‘vozdukh’ for ‘air’; there, however, are Old Church Slavonicisms, disseminated by the Greek-Catholic clergy in the 19th century.””

And I also noted that while of course Galicia is not the only source of the Ukrainian diaspora community, it did have a large influence on the community, and that in any case, my article is specifically about the Galician diaspora community (I didn’t have much contact with other communities so I am not addressing them, which I tried to make clear in my article.)

I have also written about prononciation in the Galician diasporan dialect here: http://forgottengalicia.com/the-vanishing-galician-accent-and-how-it-lingers-in-the-diaspora/

It is a common misconception that Ukrainian is somehow supposed to be closer to Russian than to Polish, for example. A Ukrainian linguist has already demonstrated this to not be the case. While Ukrainian is very close to Belarusian, it is closer to Polish (and to Slovak) than it is to Russian, while the latter has more common vocabulary with Bulgarian (and with Serbian) than with Ukrainian. Here’s one link: https://ridna.ua/2016/06/yaki-jevropejski-movy-najblyzhchi-mizh-soboyu/

Or you can also search “лексичні відстані Тищенко”

I wanted to add some words to the list.

My dad always used балакати instead of говорити, and I can never find where this comes from. He also preferred the word гарбата instead of чай. I’ll have to do my own thinking about this. I’ve been upkeeping my Ukrainian with Duolingo and sometimes my vocabulary is so much different from what they’re teaching.

Hi John, I hear the word балакати a lot in Lviv these days, it’s a colloquialism and I believe a dialectism, for as far as know it’s not used outside of western Ukraine. And interesting that your dad used гарбата for tea. That is from Polish, as “herbata” is “tea” in Polish.

My grandmother used the same words! She came from Peremyshl area in about 1928

Гербата, close to your pronunciation, I believe comes from “herbal tea.”

Do Galician (Ukrainian) speakers pronounce Veronica as Weronika (Polish) or Veronika (Russian)?

Neither this or that. Ukrainian “В” sound is something in the middle between English V and W sounds. It tends to be closer to V in Eastern parts and closer to W in Carpathian Mountains and close to them

This is fascinating. Are there also phrases that are unique to the Lviv area? My family is from Rohatyn, SE of Livi, so I assume the dialect and word choice would be similar. Thanks!

Yes, I think the dialect in Rohatyn would have been very similar. A lot of what is in the list would have been used across all of Galicia, but of course there were probably some small differences depending on what part of Galicia.

Порекомендувала до друку Науково-методична рада НУ «Львівська політехніка»

як навчальний посібник для студентів усіх спеціальностей

(протокол № 34 від 15 березня 2018 р.).

Ре ц е н з е н т и :

І. П. Ющук — д-р філол. наук, проф., завідувач катедри слов’янської філології та загального мовознавства Київського міжнародного університету;

І. М. Кочан — д-р філол. наук, проф., завідувачка катедри прикладного мовознавства Львівського національного університету ім. І. Франка;

О. П. Левченко — д-р філол. наук, проф., завідувачка катедри прикладної лінгвістики, Інституту комп’ютерних наук та інформаційних технологій НУ «Львівська політехніка».

Видано в авторовій редакції

Зубков, Микола.

Норми та культура української мови за оновленим правописом. Ділове мовлення. 3-й вид., доп. і змін. / Микола Зубков. — К. : Арій, 2020. — 608 с.

ISВN 978-966-498-622-6.

Посібник осягає основи культури спілкування, види й жанри публічних виступів. У ньому подано головніші правописні норми та правила, морфеміку й морфологію. Закцентовано увагу на особливостях уживання іменних і службових частин мови в офіційно-діловому стилі, а також на складних випадках перекладу науково-технічної, економічної та иншої термінології.

Довідник допоможе зорієнтуватися у стильовому розмаїтті сучасної літературної мови, оскільки подає та характеризує всі її стилі й підстилі. Зручні таблиці містять класифікування документів і ділення їх за признакою та назвою. Уміщено чималу кількість формулярів-взірців сучасних документів і їхніх складників із докладним описом. Система запитанків і завданків для самоконтролювання надасть змогу охочим повторити викладений матеріял.

Уперше в довіднику такого типу наведено низку посилок-виносок із пояснинами щодо призабутих, «зрепресованих», але природних для нашої мови термінних слів і словосполук, правила творення та вживання яких унормовує національний стандарт ДСТУ 3966:2009 й оновлений чинний правопис (2019).

Книжка буде надійним порадником для всіх поціновувачів українського слова.

Автор щиро завдячує членові науково-технічної комісії з питань термінології при Держстандарті України, начальнику відділу науково-технічної термінології Українського науково-дослідного інституту стандартизації, сертифікації та інформатики (1996–2006 рр.), к. т. н. В. Моргунюкові за редагування, плідне обговорювання рукопису й важливі зауваги, урахування яких дало змогу поліпшити зміст і вдосконалити наукову мову, відповідно до вимог національних стандартів ДСТУ 3966 і ДСТУ

Incidentally, “The Bukovynian Lexicon” is rather similar to that of “Galician” except with more German rather than Polish (файно-fine vs. ладно). As far as Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian being all Slavic languages and their similarities, they did not develop similarly. While Belarusian and Ukrainian languages were well on their way during X and XI Century, Russian language had its start in the XI Century with the introduction of religion, using Macedonian/Bulgarian church language that was used in liturgy, sermons and courts among the Hungro-Finish tribes of the North.

Yes, herbata is tea in Polish, presumably from herb (tea), what is the origin of this ? classical?

Chai – did that come the other way with Genghis? This part of the world is a crossroads!

Thank you for working this out in such organized detail! I love my Galician way of speaking and when we visited Ukrayina in 1996 I was happy to discover that in the Carpathian village we went to visit as it’s where both of my parents came from, people spoke exactly as we did. In the cities it was different. In the cities I also discovered surzhyk, at first believing that I had acquired an ear for Russian, lol. This is great, Areta!

Thank you, glad to hear!

I find it interesting that Ukrainian speakers in Canada have adopted “мене звати…..” instead of “я називаюся…”. My cousin, who is a teacher in Western Ukraine told me recently that the students are now being taught the latter form of introduction.

Interesting. I very rarely heard “я називаюся” in Lviv – happy to hear that this is now what is being taught here.

My grandparents were from Galicia. They both came to the USA in the late 1800’s, my grandmother with her sisters and grandfather with his father. Eventually they met, married, and moved to coal country in Pennsylvania. My dad told me he and his brothers went to English school during the day and Greek school a few nights a week. He thought they spoke Russian in their home, however, I saw a tv program about Slovakia and recognized a few words my dad used to say. Neither my brother or I were taught any languages my grandparents spoke. Are there books or audio materials you would recommend for beginners? Thank you.

Thank you

Thank you for this website. It is unusual and very interesting. Do you know of any other similar website???

C/\ABKO

Crystal Lake, Illinois

[…] View full story […]

Woah, such a loaded yet interesting conversation Areta.

On one side you have ‘Sovietized’ Ukrainians defending their dialect as a non-Polonized version and on the other side you have Western Ukrainians defending their dialect as non-Russified (is this what men in the Kremlin dream of?)

In reality both are wrong, but as a qualified linguist and someone proficient in both Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, Czech and (Mandarin-yes its a weird combo) if I was forced to choose one the latter one is correct.

It is undeniable that during the Soviet Union, Russification was standard practice, not only was there a passive Russification by prioritising professional opportunities to Russian speakers but there was of course the far more direct side e.g. the Holodomor, the Executed Renaissance, Deportations and the rewriting of dictionaries.

It is hard to imagine now, but at the turn of the 20th century all languages, including Ukrainian, Russian and Polish were not yet standardized, the forms that we speak today were determined by philologists through academic papers and by publishing dictionaries.

The Soviet politburo was well aware of this and took a serious interest, Stalin was THE Minister of Nationalities prior to Lenin’s death in 1924, they were not just devoted socialists as some Soviet apologists suggest, they were aware of the practical realities of all the republics that were part of the USSR.

Let it be clear that Ukrainians who complain of Russification of the Ukrainian language (something Luba above feels against?) may feel utterly vindicated for there are many other republics of the former USSR that complain their lexicon was distorted.

As far as Tajikistan in Central Asia, Tajik people complain words like ‘kartoshka’, ‘lyotchyk’ were artificially inserted into their language during the course of the USSR.

This is also what happened to Ukraine, ever since the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was incorporated into the USSR, Soviet academics and apparatchyky sought to cleanse the Ukrainian language of words they ironically also referred to as ‘polonisms’, a common and baseless propaganda conspiracy myth of the ‘Ruskiy mir’ is after all that Ukrainian is polluted with ‘polonisms’.

They succeeded in removing many native Ukrainian words and replacing them with words that from an etymological point of view are completely illogical ‘kanikuly’ is of Kazan tatar origin whom only ethic Russians had contact with, chemodan is of Persian origin via Turkic and again would have no natural route into Ukrainian other than via Russian, korytsya (cinnamon) is equally perplexing.

Yet, when confronted with a synonym or alternative to a hang-over from the Soviet Era many a Ukrainian dejectedly protest the alternative is a Polonism or Galicism.

This is unequivocally wrong and has become a convenient excuse for those who think that speaking Ukrainian requires simply switching the pronunciation of Russian words from a ‘g’ to a fricative ‘h’.

Over the decades, but particularly more with increasing standardization the chest of Galicisms is growing full of natural and authentic Ukrainian words, endemic to all of Ukraine and that have been repressed into being obsolete

It is not uncommon (and the position endorsed here?) that words common a century ago to all Ukrainians such as ovoči and horodyna/yaryna, vudzheny, pomerancha, tsytryna and so many more are to be dismissed as polonisms.

There are so many incoherencies in that arguement:

1. Why are they Polonisms? all of the words listed above save (horodyna/yaryna) are all common to Slovak and Czech, ovoči as fruit is even common to every single slavic language, so I think it is well established that Russian was the odd one out and that Ukraine has adopted a Russism, as it has with many other words. Or should we also call them Polonisms/Czechisms/ Slovakisms/Slavicisms

2. Many of the words accused of being Polonisms are pronounced significantly different from Polish equivalents, the word ‘proshu’ often incorrectly described as a Western alternative of bud’ laska is pronounced in Polish as proshę (with a nasal ending not anything like in Ukrainian), not to mention the fact the word ‘proshu’ can be found in Russian with a different meaning

3. These ‘polonisms’ words were often used by Ukrainian writers of the Russian empire, filizhanka was used by Kotliarevsky, tsytryna was used by Yury Yanovsky from Central Ukraine (around Kropvynytskyi) and by Russian-Jewish author Nathan Rabak when writing Ukrainian

4. Ukraine shares a massive land border, and history with Poland, is the only acceptable path of words into the Ukrainian language via its eastern borders? Almost all foreign borrowings in Polish come from German rather than Ukrainian or Russian yet we don’t see Poles clambering to remove Germanisms, West-East was arguably the direction in which ideas flowed for much of the past centuries.

I think this amazing comment I found on the internet sums it up “Я не раз помічала, що ‘галицький діалект’ виявився свого роду притулком для слів, які чомусь протрапили під репресії.”

I don’t speak Ukrainian with a palatalization of a ‘v’ into a ‘w’ as some Western Ukrainians do but I feel in the interests of linguistic accuracy I must also defend this.

This is not as has been suggested a random of influence of the Polish language, or as it was alarming written on another interesting and engaging article of this blog ‘geneological deformity’ rather the turning of a ‘v’ into a ‘w’ is unique to and prized part of the Ukrainian language, that should be preserved.

Polish people turn a broken l e.g. ‘ł’ into a ‘w’ sound, Poles do not turn their ‘v’ into ‘w’. Some contest however that because Poles say ‘małpa’ and Western Ukrainian turn ‘mavpa’ into ‘małpa’ then this proves the inflection derives from Polish. The word money in Polish and Ukrainian is a linguistic aberration, whereby the parts of each language that create a ‘w’ sound happen to align.

There are hundreds of words where the opposite occurs, Western Ukrainians or some Western Ukrainians pronounce Lviv as Lviw, this simply does not happen in Polish where it continues to be called ‘Lwów’ with a clear ‘v’ at the end.

Last names like Radziwiłł would be pronounced by Ukrainians as it is spelt in English with the ‘w’ pronounced as a ‘w’ and the ‘l’ pronounced as an l, the opposite occurs in Polish with the ‘w’ pronounced as a ‘v’ and the ‘l’ pronounced as a ‘w’.

It is likely the origin of this palatalized ‘w’ is of the same origin as the Czech au (that turns into a w) auto is pronounced ‘awto’ in Czech or the Belarusian Ў.

To be honest I really think Ukrainians in general need to stop critiquing how each other speak, its divisive and creates issues. The only forum for this should be academia, however, if anyone should be challenged to speak a more Ukrainian Ukrainian it would be where I come from, around Kharkiv or Eastern Ukraine in general. I feel that as someone that used to say call many words authentic Ukrainian words (polonisms) that this is a convenient excuse for those whose Ukrainian skills are not good or feel insecure. People that speak Ukrainian on a daily basis, make an effort to continue its usage should not have to be told how to speak a language by a person who does not use it.

Hence, in the complete opposite vein as Luba, I would please caution you from describing authentic Ukrainian words as ‘polonisms’ or even ‘galicisms’ for whilst there are like every language true dialectisms many of these words now being ascribed as ‘galicisms’ were common in the Ukrainian vernacular only a century ago, before being replaced by what are justifiably called ‘Russisms’.

Is there a reason why you refer to this language as ‘Galician’ rather than Rusyn or Ruthenian? Rusyn is its own language (not related to Russian), not some variant of Ukrainian, although it is very similar. Is there a difference between diasporic language and Rusyn?

No Rusyn is not its own language. It is a dialect and on a continuum of the Ukrainian language. The endonym Rusyn was common amongst all Ukrainians up to the 17-18th centuries, it is simply a historic term for Ukrainians. Just as Moravians is for Czechs. The concept of Rusyn identity and language was historically sponsored by the Tsarist regime and now funded by current Russian authorities. Many members of the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine also foment this identity. The only differentiating features of Rusyn dialect are the occassional use of Slovak or Hungarian words.

Hi, I loved the article, there is just one small typo: “Hungry” 🙂 please, correct it to “Hungary”. Keep up the good work.

My father-in-law emigrated to Australia in 1948. We have some photos with cursive writing on the back which we believe is written in Galician. He was from Korets originally. Unfortunately we have no way of translating these writings as my wife only learnt traditional Ukranian many years ago. I was hoping that someone may be able to help if I send you the writings in question?

Korets is not Galicia – it’s Volyn. BTW I believe I can help you with the translation

Hi Roman,

Thank you for the kind offer, and the interesting information, but we did manage to get it translated. It was in fact badly written Ukrainian and a personal note from a relative. Apologies for the late reply.