By Chris Wilkinson

A good argument could be made that obsession is little more than ambition taken to extremes, ambition to do something way beyond what has ever been done before. Obsessions by their very nature are all consuming. Thus obsessives find their lives for better or worse (usually worse) ruled by a person or goal they have become fixated upon. The obsession rules the person rather than the other way around. In effect they become a slave to their obsession. At some point they usually come to regret their obsession, wishing they could eradicate it from their thoughts and memory. This is impossible until the obsession has run its course. Obsessives are capable of doing great things, achieving the impossible. Conversely, they are more often than not, defeated by the impossible. The problem with obsessives is that they believe less in themselves, than they believe in their obsession.

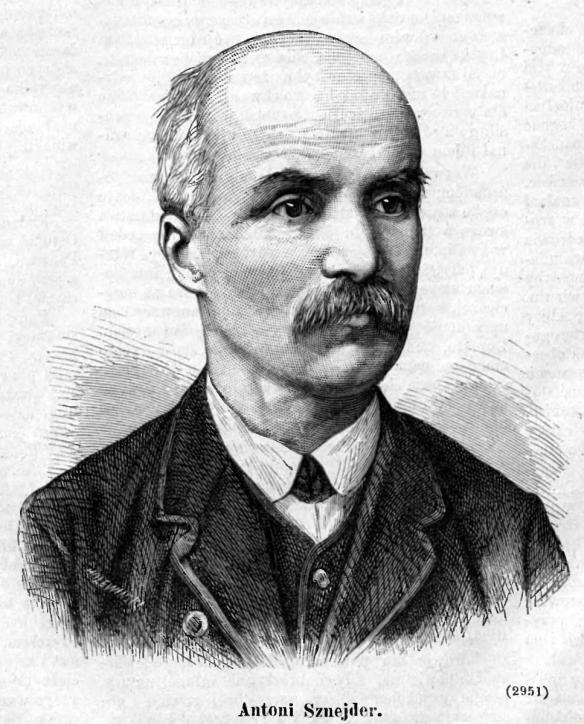

One of the greatest obsessives in the history of Lviv was a man by the name of Antoni Schneider. He imagined a project of such scale that it scarcely seemed possible. That did not stop Schneider from trying to create and eventually be defeated by The Encyclopedia of Expertise on Galicia.

An Exhaustive Encyclopedia of a Make Believe Province

The Austrian administered province known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria was just short of a hundred years old when Schneider announced his project in 1868. While the land that made up the province had existed since time immemorial, the idea of the Kingdom was created from an old and obscure claim made new. The Austrians took the name from a medieval title held by King Andrew II of Hungary who had conquered the region during the twelfth century. Though the Hungarian crown lost the land in rather short order, the title came in handy for the Austrians over 500 years later. They felt the need to show a legitimate historical claim to the region. This was in response to the fact that they had taken the region in the first partition of Poland. To rule the inhabitants, they needed legitimacy. Since Austria also ruled Hungary, they decided to excavate the old Hungarian claim to the kingdom from the dustbin of history. The Austrians spent a considerable amount of time and effort recreating Galicia in their own image. In this way they made history and also made it up.

A multi-volume encyclopedia cataloging in exhaustive detail every aspect of the province would further legitimize Galicia. Schneider’s idea was his own, but it was certainly informed by this process. The encyclopedia would be a mammoth undertaking. Schneider was to shoulder nearly all of a superhuman workload. It would provide holistic coverage of the province, with everything from history to statistics to scientific topics receiving in-depth coverage. He professed that the encyclopedia was his way of paying homage to his “fatherland”. This seeming labor of imperial love came from a man who two decades before had been part of open rebellion against the Habsburgs.

Oddly enough, Schneider was ethnically half-German and half-Polish, but the encyclopedia was to be a Polish language work. This made sense from both a political and readership standpoint. Political, since the province had just gained autonomous status. Poles would heretofore be the ruling and administrative class in Galicia. To gain a wide readership it would be written in Polish, since that was now going to be the lingua franca of the province.

A Most Ambitious Madness

One can only speculate to the degree that manic imagination and frenetic energy played a role in Schneider’s conception of the project. He was largely self-taught. Due to family financial woes he was unable to complete high school. For a time he worked as a clerk for a literary journal, gaining some valuable real world experience in the writing profession.

Schneider then became caught up in the 1848 Hungarian Revolution fighting on the side of rebellion. This landed him in jail, but it turned into a fortuitous stroke of luck. He shared a prison cell with a Hungarian historian, Joseph Teleki. Their conversations must have encouraged him to do research and learn more about the past.

After he was freed, Schneider toured the countryside around Lviv taking an interest in among other things, castles and ruins. Then in the 1860s he started publishing articles of stories about places in Galicia. This all led up to the encyclopedia that was to provide a one stop resource for detailed knowledge of almost any subject pertaining to Galicia. The fact that one man conceived and then attempted to carry out this idea speaks volumes about Schneider’s mindset.

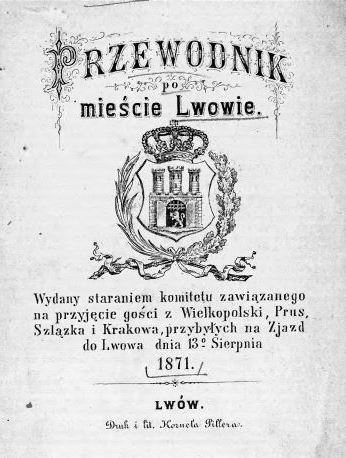

Unfortunately, even the most enduring obsession has its limits. Schneider openly stated that the project would take thirty years to complete. That turned out to be a low estimate as the actual production of the first two volumes would show. The volume dealing with letter A took three years to write and was published in 1871. In the same year Schneider also published a Guide to Lwów. The letter B volume appeared in 1874. At this rate the entire project would take another 72 years to complete. In 1874 Schneider was already 49 years old.

Sometime during these years it must have dawned on him that there was no way he would ever complete the encyclopedia. The euphoria he had first experienced with his grandiose dream abated. Subscriptions to the encyclopedia lagged. There was a decided lack of public interest. It turned into an all or nothing enterprise. Sure volumes A and B had been completed, but this was only equivalent to less than ten percent of the entire project. What was the use of doing a volume C? It was just another drop of knowledge in an unfathomable ocean of information.

The Darkest Side Of Obsession

Schneider’s dream descended into darkness. It was a failure made that much worse by obsession. His life had become the encyclopedia, without it he was nothing. He was unable to come close to finishing the project, even though he continued collecting information for every subject of note. His information gathering expanded to the history of the Bukovina province, adjacent to Galicia.

All of this work has provided a rich archival source that is still used by researchers today, but what good did that do Schneider at the time? His thoughts of the future would have been aligned with the fact that his life’s work could never be completed.

In 1880, he committed suicide by shooting himself. This was the final, mortal blow to a dream that had died long before. Schneider had not been able to finish his work, but it had finished him.

Source: Europe Between East and West